As winter fades into spring in the Northern Hemisphere, people eagerly shed their heavy coats and spend more time outside. But as temperatures keep rising in some parts of the world, we’re likely to head inside to enjoy the comfort of air conditioning. Before it became common in homes across the United States, artificial cooling in theaters helped people escape the summer heat. So, if you’re able to enjoy a comfortable indoor show this summer, take a moment to thank David Crosthwait. This pioneering engineer designed the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system for New York’s famous Radio City Music Hall in the 1930s and holds dozens of patents related to heating and cooling systems. Over a career spanning more than five decades, Crosthwait helped make indoor climate control a familiar feature of modern life.

The Dawn of an Air-Conditioned Century

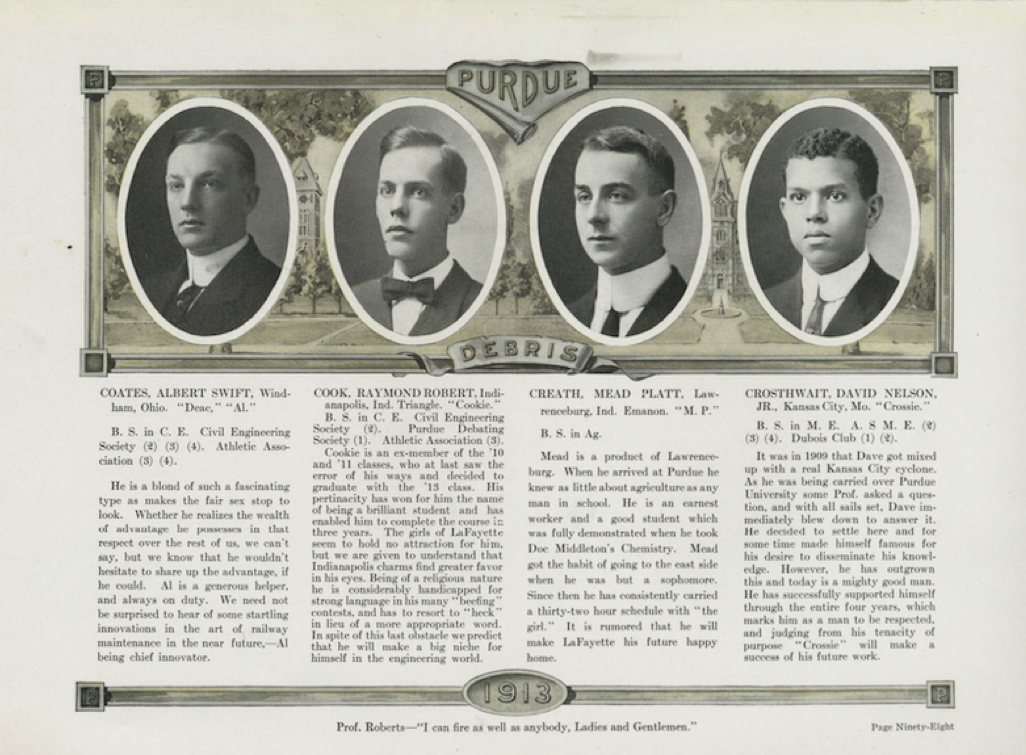

David Crosthwait was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on May 27, 1898. After growing up in Kansas City, Missouri, he attended Purdue University, where he earned a master’s degree in engineering in 1920. In 1925, he joined the C.A. Dunham Company, eventually becoming its director of research. This Iowa firm produced heating systems and was involved with the emerging technology of air conditioning.

A 1913 Purdue University yearbook photo of David Crosthwait (rightmost photo). Image rights and credits to the Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

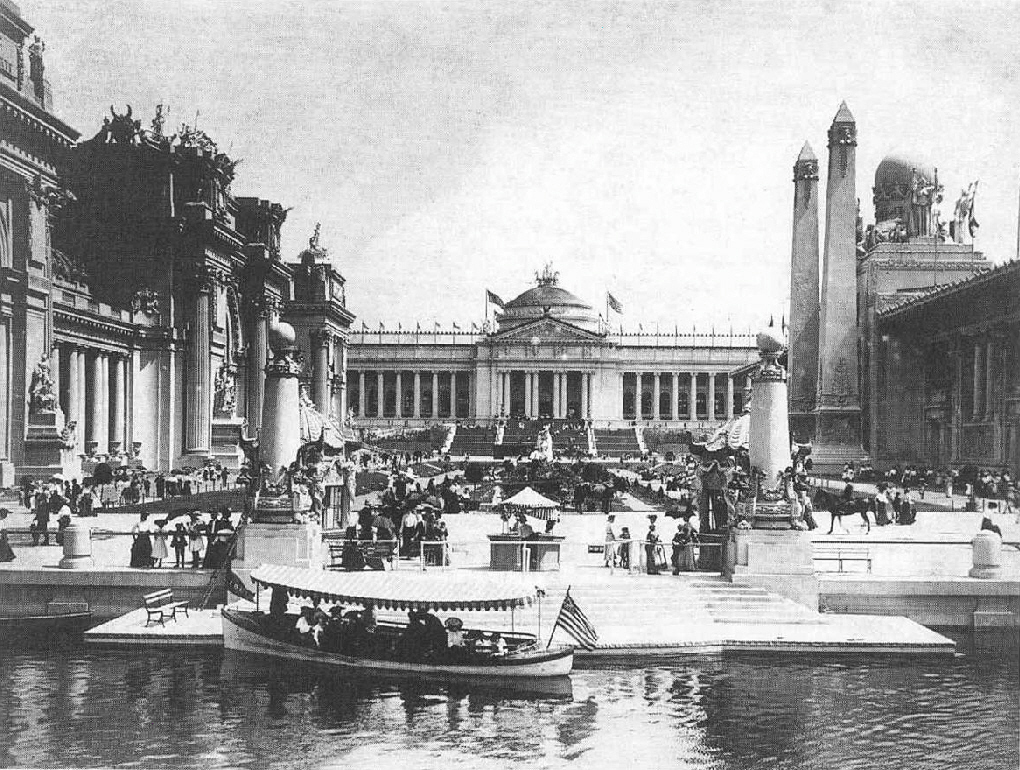

While humans have been heating their environments since the invention of fire, artificial cooling is a relatively recent invention. Some 19th-century inventors were able to demonstrate the principles of mechanical refrigeration, but not until Willis Carrier patented his “Apparatus for Treating Air” in 1902 could indoor heat and humidity be controlled by machines. These early air conditioners were relatively expensive and inefficient, which limited their use to large-scale commercial applications. Members of the general public first enjoyed an artificially cool breeze at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, which featured an air-conditioned 1000-seat auditorium.

Buildings at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Image in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

These early cooling systems, which were usually retrofitted to existing heating ductworks, caused some strange, new problems. As noted in the U.S. Department of Energy article, blowing cold air through a theater’s floor vents could lead to “hot, muggy conditions at upper levels and much colder temperatures at lower levels, where patrons sometimes resorted to wrapping their feet with newspapers to stay warm.”

Helping the “Roaring ’20s” Keep Their Cool

The decade of the 1920s saw many once-novel experiences become part of everyday life. More people than ever before were driving cars, listening to radios, and watching movies — often in air-conditioned theaters. In 1922, Willis Carrier’s eponymous company installed improved cooling systems in theaters in Los Angeles and New York. This led to a boom in air conditioning installations, as well as efforts by engineers to make these systems more reliable and efficient.

Radio City Music Hall, which is part of the massive Rockefeller Center complex in New York City. The original HVAC system for Rockefeller Center was designed by David Crosthwait. Image by ajay_suresh, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

David Crosthwait was an important contributor to the rapid advance of heating and cooling technologies. As part of his work for C.A. Dunham, he developed an improved thermostat, a differential vacuum pump, and other innovative mechanisms and system designs. In the 1930s, Crosthwait designed the climate control system for New York’s Rockefeller Center complex, including its spectacular theater, Radio City Music Hall.

The dramatic interior of the Radio City Music Hall theater. Image by Smart Destinations, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Recognizing Crosthwait’s Accomplishments

Over the course of his long career, Crosthwait would receive 39 U.S. patents and 80 foreign patents for HVAC devices. He also wrote manuals and codes to guide the design, installation, and maintenance of such systems. He retired from corporate life in 1971, when he also became the first Black fellow of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). This is significant, as Crosthwait’s contributions to public places, such as theaters, came during an era when many American theaters were racially segregated. Before the 1960s, some of the businesses that installed C.A. Dunham HVAC systems may not have admitted the man who designed those systems.

For the next five years, Crosthwait taught at his alma mater of Purdue before passing away in 1976. Today, we can recognize the impact that David Crosthwait has had on climate control systems by wishing him a happy birthday!

Further Reading

- Learn more about David Crosthwait and the development of HVAC technology:

- Examples of how simulation is used for climate control R&D:

Comments (0)